Analyses of data acquired by the NASA Dawn mission show that the surface of large asteroid Ceres is rich in hydrogen in the form of phyllosilicates, water ice, and perhaps organic matter. Differences between Ceres’ surface elemental composition and that of the primitive CI chondrites suggest Ceres underwent ice-rock fractionation or formed from a different reservoir than the CI parent body. Composition data acquired by Dawn provide further constraints on Ceres’ origins, hydrothermal evolution, and present state, placing Ceres in context with other icy, solar system bodies.

February 03, 2017: Characterizing Middle And Outer Solar System Minor Bodies As Probes For Solar System Evolution

Many current theories posit a period of chaotic dynamical alterations throughout the middle and outer Solar System, during which the orbital architecture of the gas and ice giants changed drastically and the remnant planetesimals from planet formation were scattered. Using photometry, spectroscopy, and magnitude distribution analysis to study the present-day minor bodies that occupy this region namely, Jupiter Trojans, Hilda asteroids, Kuiper Belt objects and Centaurs we can compare the properties of the various populations and begin to evaluate our understanding of Solar System evolution.

January 27, 2017: Probing The Comet-Asteroid Continuum

The era of modern astronomy is unfortunately not long enough to cover the typical lifetime of comets. However, comets produce dust which is potentially detectable as meteor activity at the Earth. Here I discuss the effort to understand cometary aging by examining different parts of the evolution spectrum of Jupiter-family comets (JFCs) by combining telescopic and meteor observations.

The iPLEX Winter 2017 Guest Speaker Schedule

The iPLEX Winter 2017 Guest Speaker Schedule:

Please join us on Fridays from 12 to 1pm in UCLA Geology Building (Room 3-814), followed by lunch 1 to 2pm.

The first and last days of classes for the Winter 2017 are January 9th 2017 and March 17th 2017, respectively.

Jan 13: No speaker/talk this week

Jan 20: Margaret Pan (MIT) “Eccentric rings and disks”

I’ll describe two observationally-motivated projects on eccentric systems of colliding particles. First, I’ll discuss a derivation for the mass of the rings orbiting the minor planet Chariklo, and some implications for how those rings formed; second, I’ll discuss azimuthal brightness variations in eccentric debris disks in the context of the very well observed Fomalhaut disk.

Jan 27: Quan-Zhi Ye (Caltech) “Probing the comet-asteroid continuum”

The era of modern astronomy is unfortunately not long enough to cover the typical lifetime of comets. However, comets produce dust which is potentially detectable as meteor activity at the Earth. Here I discuss the effort to understand cometary aging by examining different parts of the evolution spectrum of Jupiter-family comets (JFCs) by combining telescopic and meteor observations.

Feb 03: Ian Wong (Caltech) “Characterizing middle and outer solar system minor bodies as probes for Solar System evolution”

Many current theories posit a period of chaotic dynamical alterations throughout the middle and outer Solar System, during which the orbital architecture of the gas and ice giants changed drastically and the remnant planetesimals from planet formation were scattered. Using photometry, spectroscopy, and magnitude distribution analysis to study the present-day minor bodies that occupy this region namely, Jupiter Trojans, Hilda asteroids, Kuiper Belt objects and Centaurs we can compare the properties of the various populations and begin to evaluate our understanding of Solar System evolution.

Feb 10: Thomas Prettyman (PSI) “Evidence for aqueous alteration and ice-rock fractionation on (1) Ceres”

Analyses of data acquired by the NASA Dawn mission show that the surface of large asteroid Ceres is rich in hydrogen in the form of phyllosilicates, water ice, and perhaps organic matter. Differences between Ceres’ surface elemental composition and that of the primitive CI chondrites suggest Ceres underwent ice-rock fractionation or formed from a different reservoir than the CI parent body. Composition data acquired by Dawn provide further constraints on Ceres’ origins, hydrothermal evolution, and present state, placing Ceres in context with other icy, solar system bodies.

Feb 17: Dan Cziczo (MIT) “Ice Nucleation: From the Earth to Mars and Beyond”

Ice nucleation in the Earth’s atmosphere is known to be an important factor in climate, chemistry, and precipitation. By mimicking that planet’s atmosphere, we can leverage tools for terrestrial studies of ice clouds to understand the Martian water and carbon cycles. Recent observations show clouds to be present around exoplanets as well. Although measurements are much more uncertain, these technologies can help elucidate the atmospheres of these distant planets.

Feb 24: Danielle Hastings (UCLA) & David Jewitt (UCLA) “The Rotation Period of Hi’iaka, Haumea’s Largest Satellite” (Hastings) & “Rotationally Disrupting Bodies” (Jewitt)

Hastings: Using relative photometry from the Hubble Space Telescope and Magellan, we have found that Hi’iaka, the largest satellite of the dwarf planet Haumea, has a rotation period of ~9.8 hours. This surprisingly short period, ~120 times faster than its orbital period, creates new questions about the formation of the Haumea system and possible tidal evolution.

Jewitt: I will present observations suggesting the role of rotational disruption in the solar system.

Mar 03: Eric Mamajek (JPL) “A Transiting Extrasolar Ring System”

I’ll discuss the discovery and characterization of the “J1407” (V1400 Cen) system and its eclipsing complex ring system. J1407 is an otherwise unremarkable ~15 Myr-old pre-main sequence solar-mass star lacking infrared excess. The disk/ring system transiting J1407 is tenths of an AU in size with approximate mass similar to that of the Earth, and the best models thus far require dozens of rings. The system is intermediate in size and mass between Saturn’s rings and circumstellar disks, and may represent the first example of a protoexosatellite disk and indirect evidence of exomoon formation.

Mar 10: Roger Fu (Harvard University) “Meteorite Paleomagnetism”

Magnetic fields permeated the partially ionized gas of the solar nebula and may have also been generated by metallic core dynamos in early-forming planetesimals. I will talk about paleomagnetic experiments on meteorites that yield information on the evolution of the protoplanetary disk and the accretion of planetary bodies.

Mar 17: Zhaohuan Zhu (UNLV) “Young Planets in Protoplanetary Disks: Theory Confronts Observations”

Recently commissioned telescopes and instruments (e.g., Subaru, GPI, VLA, ALMA, EVLA) are now finally able to resolve the protoplanetary disk down to the AU scale, and a rich variety of disk features have been revealed. In this talk, I will discuss how these observations can constrain protoplanetary disk dynamics and planet formation theory.

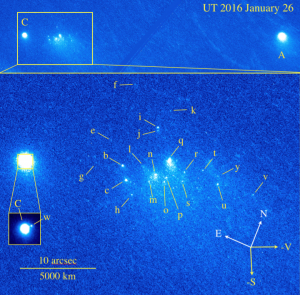

The Disintegration of Comet 332P/Ikeya-Muramaki

Astronomers have captured the sharpest, most detailed observations of a comet breaking apart 67 million miles from Earth, using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. The discovery is published online today in Astrophysical Journal Letters.In a series of images taken over three days in January 2016, Hubble revealed 25 building-size blocks made of a mixture of ice and dust that are drifting away from the comet at a leisurely pace, about the walking speed of an adult, said David Jewitt, a professor in the UCLA Department of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences and the UCLA Department of Physics and Astronomy, who led the research team.The observations also suggest that the roughly 4.5-billion-year-old comet, named 332P/Ikeya- Murakami, or Comet 332P, may be spinning so fast that material is ejected from its surface. The resulting debris is now scattered along a 3,000-mile-long trail, larger than the width of the continental U.S.These observations provide insight into the volatile behavior of comets as they approach the sun and begin to vaporize, unleashing powerful forces.“We know that comets sometimes disintegrate, but we don’t know much about why or how,” Jewitt said. “The trouble is that it happens quickly and without warning, so we don’t have much chance to get useful data. With Hubble’s fantastic resolution, not only do we see really tiny, faint bits of the comet, but we can watch them change from day to day. That has allowed us to make the best measurements ever obtained on such an object.”The three-day observations show that the comet shards brighten and dim as icy patches on their surfaces rotate into and out of sunlight. Their shapes change too as they break apart. The icy relics comprise about four percent of the parent comet and range in size from roughly 65 feet wide to 200 feet wide. They are separating at only a few miles per hour as they orbit the sun at more than 50,000 miles per hour.

The Hubble images show that the parent comet changes brightness frequently, completing a rotation every two to four hours. A visitor to the comet would see the sun rise and set in as little as an hour, Jewitt said.

The comet is much smaller than astronomers thought, measuring only 1,600 feet across, about the length of five football fields.

Comet 332P was discovered in November 2010, after it surged in brightness and was spotted by two Japanese amateur astronomers, Kaoru Ikeya and Shigeki Murakami.

Based on the Hubble data, the research team suggests that sunlight heated up the comet’s surface, causing it to erupt jets of dust and gas. Because the nucleus is so small, these jets act like rocket engines, spinning up the comet’s rotation, Jewitt said. The faster spin rate loosened chunks of material, which are drifting off into space. The research team calculated that the comet probably shed material over a period of months, between October and December 2015.

Jewitt suggests that some of the ejected pieces have themselves fallen to bits in a kind of cascading fragmentation. “Our analysis shows that the smaller fragments are not as abundant as one might expect based on the number of bigger chunks,” he said. “This is suggestive that they’re being depleted even in the few months since they were launched from the primary body. We think these little guys have a short lifetime.”

Hubble’s sharp vision also spied a chunk of material close to the comet, which may be the first salvo of another outburst. The remnant from still another flare-up, which may have occurred in 2012, is also visible. The fragment may be as large as Comet 332P, suggesting the comet split in two. But the icy remnant wasn’t spotted until Dec. 31, 2015, by the Pan-STARRS (Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System) telescope in Hawaii.

That discovery prompted Jewitt and colleagues to request Hubble Space Telescope time to study the comet in detail. Around the same time, astronomers worldwide began to notice a “cloud of nebulosity” near the comet, which Hubble later resolved into the 25 pieces.

“In the past, astronomers thought that comets die when they are warmed by sunlight, causing their ices to simply vaporize away,” Jewitt said. Either nothing would be left over or there would be a dead hulk of material where an active comet used to be. But it’s starting to look like fragmentation may be more important. In comet 332P we may be seeing a comet fragmenting itself into oblivion.”

The researchers estimate that comet 332P contains enough mass to endure another 25 outbursts. “If the comet has an episode every six years, the equivalent of one orbit around the sun, then it will be gone in 150 years,” Jewitt said. “It’s just the blink of an eye, astronomically speaking. The trip to the inner solar system has doomed it.”

The icy visitor hails from the Kuiper belt, a vast swarm of objects at the outskirts of our solar system. These icy relics are the leftover building blocks from our solar system’s construction. After nearly 4.5 billion years in this icy deep freeze, chaotic gravitational perturbations from Neptune kicked comet 332P out of the Kuiper belt, Jewitt said. As the comet traveled across the

solar system, it was deflected by the planets, like a ball bouncing around in a pinball machine, until Jupiter’s gravity set its current orbit, he said.

Jewitt estimates that a comet from the Kuiper belt gets tossed into the inner solar system every 40 to 100 years.

Co-authors include Harold Weaver, Jr., research professor at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

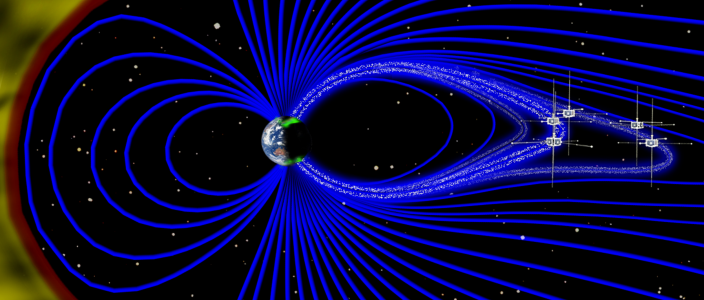

EPSS’s Emmanuel Masongsong’s Figure Published in Nature Physics

Image caption: An artist’s rendering of the magnetosphere in cross-section, with the sun and solar wind on the left and magnetic field lines emanating from the Earth in blue. The five THEMIS probes were well-positioned to directly observe one particular magnetic field line as it moved back and forth every six minutes. This magnetic field motion caused electrons (white dots) to stream along the field line and enter Earth’s north and south poles, brightening a specific region of the aurora. Credit: E. Masongsong, UCLA EPSS, NASA EYES.

Auroras Dance to the Pulse of Earth’s Magnetic Field

by Emmanuel Masongsong, UCLA EPSS/IGPP/iPLEX

The majestic aurora has captivated humans for millennia, yet the mysterious lights’ electromagnetic nature and connection to solar activity were only realized in the last 150 years. Detailed study of the aurora has finally become possible in recent decades with coordinated multi-satellite observations, and worldwide networks of ground-based magnetic sensors and cameras. Using data from NASA’s THEMIS mission, an international team of scientists observed Earth’s vibrating magnetic field at an altitude of 40,000 miles, more than 5 times the Earth’s diameter, while simultaneously capturing the northern lights dancing in the night sky over Canada. Their findings, reported in the journal Nature Physics, are the first to directly map the back-and- forth motion of this distant magnetic field and the resulting electrical currents to a particular region of brightening aurora in Earth’s upper atmosphere. This is an important link in understanding and eventually predicting how solar activity and space electricity can impact our technological infrastructure.

The Earth is connected to the sun via the solar wind, an outward flow of electromagnetic radiation and charged particles (plasma) that affects all the planets, moons, comets, and asteroids in our solar system. These interactions, collectively known as space weather, include solar flares and violent plasma eruptions that could jam radio signals, damage weather, communications and GPS satellites, or even disable our global electrical power grid. Luckily for us, Earth has a spinning, molten metal core that generates a magnetic force field known as the magnetosphere. Magnetic field lines, like immense loops that extend outward from the Earth’s north and south poles, form a giant protective bubble that shields us from most harmful space weather.

Under the right conditions, however, some solar wind particles and energy can enter the magnetosphere and subsequently be released in powerful bursts that can power the auroras, called a substorm. The magnetic field lines surrounding our planet vibrate wildly and mobilize the surrounding plasma, causing electrons to stream along the magnetic field lines until they fall into Earth's poles. The electrons collide with atmospheric oxygen and nitrogen atoms, which then emit the familiar green and red/blue colors of the aurora. This process is like a cosmic electric guitar string, whose motion is converted to an electrical current that flows into a distant amplified speaker, but instead of a note it results in an epic plasma light show!

In 2007 NASA launched THEMIS’s five satellites to make coordinated measurements of space plasmas and ground auroras, in order to understand this energy release. In the study reported in Nature Physics, the space and ground assets were particularly well-positioned to capture the motion of the oscillating magnetic field lines together with the aurora they produced. The oscillation frequency was a mere one cycle every six minutes, yet the field line stretched back and forth by as much as two Earth diameters and the power produced, about 10GW, dwarfed the generating capacity of the largest nuclear power plants. Ground-based magnetic sensors across Canada and Greenland recorded the inflowing electrical currents, while specialized all-sky cameras captured the aurora as it brightened and dimmed, appearing to dance in lock-step with the six minute period of the vibrating magnetic field line. To verify this correlation, the researchers compared the electromagnetic energy released deep in the magnetosphere with the amount dissipated in the Earth’s upper atmosphere. “We were delighted to see such a strong match,” said Evgeny Panov, lead author and researcher at the Space Research Institute, of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Graz. “These observations reveal the missing link in the conversion of magnetic energy to particle energy that powers the aurora.”

The most intense geomagnetic storm on record occurred in 1859 when space weather phenomena affected few people, whereas today a broad range of industries and infrastructure would be crippled by such a space storm. With the continued growth of the commercial space industry, space tourism, and increasing dependence on GPS positioning for automated cars and aircraft, accurate space weather forecasting and alerts are becoming ever more crucial. THEMIS is a key component of this research fleet, refining our ability to make higher-fidelity space weather models. “Even after nearly ten years, the probes are still in great health, and our growing network of magnetometers and all-sky cameras continue to generate high quality data,” said Vassilis Angelopoulos, co-author and THEMIS principal investigator at UCLA.

THEMIS is part of NASA’s Explorer program, managed by the Goddard Space Flight Center. UC Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory is responsible for mission operations and built several of the on-board and ground-based instruments. Austria, Canada, France and Germany contributed instrumentation, operations and science. ATK (formerly Swales Aerospace), built the THEMIS spacecraft. The all-sky imagers and magnetometers are jointly operated by UC Berkeley, UCLA, University of Calgary, and University of Alberta, Canada.

iPLEX-MUST Fellows Program in Planetary Science

iPLEX-MUST Fellows Program in Planetary Science

University Involvement

Host Department:

Institute for Planets and Exoplanets (iPLEX)

Department of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences (EPSS)

Contact: Prof. David Jewitt, Director of iPLEX, jewitt@ucla.edu

Partnering University:

Macau University of Science and Technology (MUST)

Contact: Prof. Kwing Chan Lam, Director Space Science Institute, klchan@must.edu.mo

The iPLEX-MUST Fellows Program

Visitors (graduate students, postdocs and junior faculty) from the Macau University of Science and Technology (MUST) will, through extended stays at UCLA, interact with our planetary scientists under the UCLA iPLEX (Institute for Planets and Exoplanets) umbrella. Participants will visit in pairs (6 people per year, 2 people per academic quarter) and stay for one quarter each. The program objective is to learn directly about the aims and the conduct of modern planetary science from established UCLA practitioners. Fellows are expected to participate in the life of the department by attending public seminars and colloquia, and it is hope that they will take the opportunity to interact with UCLA planetary scientists in research discussions. iPLEX Fellows will participate in the development of a scientific mini-workshop, to be held on the UCLA campus, with attendance funded through this program.

Useful Links

iPLEX: http://planets.ucla.edu/about/

SSI/LPSL: http://www.must.edu.mo/en/ssi-

EPSS: http://epss.ucla.edu/

MUST: http://www.must.edu.mo/en/

UCLA Planetary Science-Related Faculty & Their Interests:

Vassilis Angelopoulos, Professor in EPSS, space physics, Themis, Artemis, CubeSat program

Jonathan Aurnou, Professor in EPSS, fluid dynamics, planetary convection, planetary magnetic fields, laboratory simulation

Brad Hansen, Professor in P&A, physics of planetary formation, disks, exoplanets, theory

David Jewitt, Professor in EPSS and P&A, planetary astronomy, primitive bodies, solar system formation

Jean-Luc Margot, Professor in EPSS, dynamics, radar astronomy

Kevin McKeegan, Professor in EPSS, geochemistry and cosmochemistry, solar wind, meteorites, origin of solar system

Smadar Naoz, Assistant Professor in Astronomy, planetary and stellar dynamics

William Newman, Professor in EPSS, mathematical physics, planetary dynamics

David Paige, Professor in EPSS, planetary ice, Moon, Mercury, microphysics and thermophysics of regoliths, spacecraft investigator

Gilles Peltzer, Professor in EPSS, remote sensing from orbit

Chris Russell, Professor in EPSS, space physics, magnetometers, DAWN asteroid mission

Marco Velli, Professor in EPSS, Space physics, solar physics, solar wind acceleration physics, Solar Probe

Hilke Schlichting, Associate Professor in EPSS, planetary dynamics, formation of solar system

An Yin, Professor in EPSS, planetary tectonics, icy satellites, laboratory simulations

Edward Young, Professor in EPSS, geochemistry and cosmochemistry, origin of water

October 8th, 2016: International Observe the Moon Night

Please join us on the evening of Saturday 08 October, 2016 from 7 to 9 PM to participate and celebrate the 2016 edition of International Observe the Moon Night! We will have telescopes set up on the roof (9th floor) of UCLA’s Mathematical Sciences Building. It’s FREE, open to the public, and you’ll be able to observe the Moon (weather permitting).

Please visit http://planets.ucla.edu/outreach/iotmn2016/ for more information and updates.

October 28th, 2016: Bi-stability of Earth and what life may have to do with it

We consider a model of the evolution of the Earth including the water cycle and continental growth along with mantle convection and thermal evolution. The water cycle and continental growth and erosion are strongly non-linear feedback cycles that are coupled through the subduction of water carrying sediments and oceanic crust. Mantle viscosity is taken temperature and water concentration dependent. We plot our results in a series of phase planes spanned by mantle water concentration and continental coverage. The system starts with one fixed point in the phase plane and evolves to three fixed points (attractors) after 2Ga. Of the three fixed points two are stable and one is unstable. The unstable fixed point represents the present Earth while the other two represent planets covered either mostly with oceans or mostly with continents. To model the effect of the biosphere we reduce the erosion rate while keeping other parameters constant. We find that in the latter case the system would evolve away from the unstable fixed point towards the mostly ocean world. One may speculate about the climate and the tectonic modes of these alternative Earths.

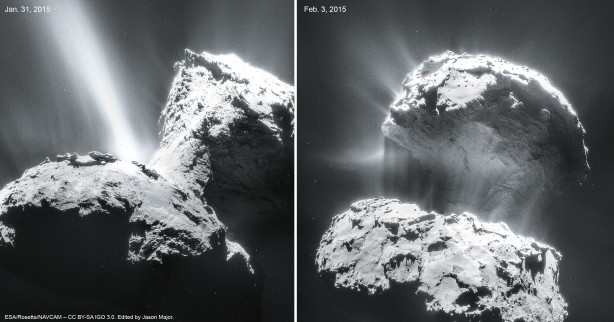

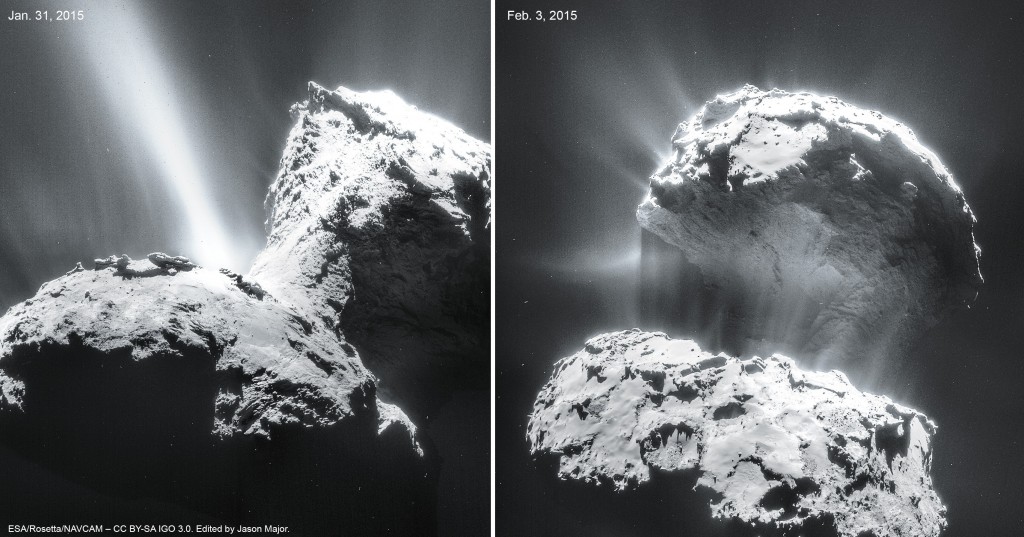

December 2nd, 2016: Comet formation theories in the light of the Rosetta mission

Measurements from the Rosetta spacecraft at comet 67P show a low density, bilobate body containing volatile gases in addition to water. I will discuss implications of the Rosetta data for comet formation models.